A spanner in the works?

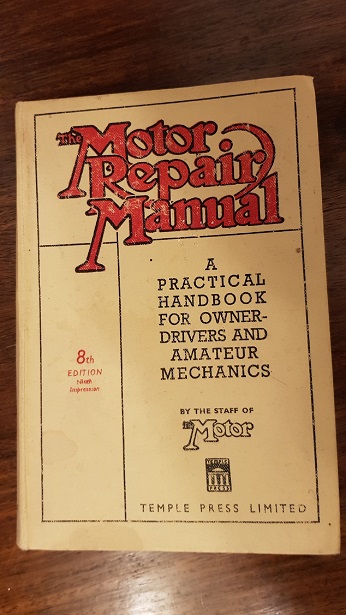

I was visiting a classic car show recently and chanced across The Motor Repair Manual, a book for the home mechanic dating from the 1930s.

The term DIY wasn’t invented back then, but the sub title A Practical Handbook for Owner Drivers And Amateur Mechanics makes the intended readership clear. The first section deals with the tools and equipment the home mechanic should expect to have in his workshop … the 1930s home mechanic is, of course, a chap.

Apart from the spanners, drills and hammers you’d expect, advice is given on choosing a good lathe (of course you need one – how else would you obtain a washer?) along with guidance on the furnace you need for annealing, tempering and case hardening metals – essential skills for making bushes and bearing scrapers or flanging pipes.

All this reminded me how much car owners were expected to do to keep their cars on the road; it was intriguing to see the classics at the show, and to recall how many British manufacturers encouraged the driver to be his own mechanic by providing a pretty comprehensive tool kit with the car.

This was not just wheel changing essentials such as a jack and wheel brace. Screwdrivers, adjustable wrench, a big hammer (always a mechanic’s friend) and of course, the inevitable grease gun, were all tucked away for use by the owner.

Concealing the tool kit led to some innovative designs as well; a 1933 Singer, more or less contemporary with the book, shows an impressive array of tools mounted on a tray under the bonnet, while other car makers installed trays or secret drawers. The practice of supplying a tool kit continued after the war.

Triumphs came with a tool roll in the boot, as did MG cars. The Sunbeam Talbot had a panel covering the inside of the boot lid which let down to reveal jack, stirrup pump, wheel-brace, starting handle and grease gun. Rover continued to supply a comprehensive set of spanners, screwdrivers and pliers, along with body touch-up paint, in a special drawer right up to the last of the 3.5 litre saloons in 1973.

My own fascination with the mechanical bits of cars started in the era of proper car toolkits, feeler gauges, tappet spanners and the smell of Swarfega!

Grease guns were mandatory since all cars had various points on the chassis and suspension which must regularly be lubricated. The points were called grease nipples, much to the sniggering amusement of adolescents passing their father the spanners on a weekend afternoon.

More upmarket owners weren’t expected to get their hands dirty of course, chassis lubrication on Rolls Royce and Bentley cars was by means of a pedal operated pump which the owner (or maybe chauffeur) had to press every so often. This was also featured on some MGs. The MG Y even had the Smiths Jackall built in hydraulic jack system, operated from the driving seat and advertised as making it simple for the owner to adjust the brakes, as well as for wheel changes.

My interest with mechanical details evolved into a job and many years ago I was an AA patrolman, working on the cars which now grace the aisles of the show.

Triumphs were always a favourite of mine; not because of their looks, performance or handling, but because with the forward opening bonnet raised, you had a very handy seat on the front wheel while working on the engine.

Today, even the wheel-changing kit is vanishing as car makers wean us off our desire for a spare wheel.

All my current Mercedes has is an electric tyre pump and a can of sealant; although BMW and Mercedes-Benz did carry on with tool kits long after the British, still supplying some models with a decent array of spanners to get the owner out of trouble until well into this century.

Is this progress? Well, yes. Modern cars need far less attention than those of my youth; no nipples to grease, no tappets to adjust, no contact breakers to clean.

A service is now an oil and filter change and a visual inspection of everything else. Most things under the bonnet are electronic and run by computers, the remaining mechanical bits last for tens of thousands of miles, rust is rare and reliability is more or less taken for granted.

They go the equivalent of half way around the world before any servicing is needed and if we take a few minutes to check the levels regularly, they can soldier on to astronomical mileages.

Tool kit? It’s in the shed with the lathe and the furnace!

By Tim Shallcross, IAM RoadSmart head of technical policy and advice